Summary

Forest Bank attempts to blend economic and ecological objectives by protecting valuable habitats and watersheds and executing ecologically sound forest management that yields reasonable financial return to landowners. Landowners’ preferences, economies of scale in management operations across fragmented forest landscapes and Forest Bank’s prudent style of timbering should produce a steady flow of revenue that covers both its management costs and the annual returns paid to landowners. Timber harvests are the main source of financial income but carbon offsets and green labels (e.g. FSC-certification) can provide additional revenue to the Forest Bank. Payments to landowners are delivered once a year. A new forest inventory is performed after each timber harvest in the property or every ten years, whichever comes first, and annual payments to the landowner (depositor) are adjusted accordingly. Forest Bank program was initiated by the largest conservation organization in the US, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), in 2002 and has since been running in two states: Indiana and Virginia. In addition, plans or feasibility studies have been made e.g. in Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota and New York. It was initially projected that in favorable conditions the Forest Bank could become a self-funding mechanism for conservation. The Virginia Forest Bank is financially self-sufficient but the Indiana Forest Bank receives some financial support from the regional TNC office. The landowners can retain ownership of the underlying land but the development rights (e.g. construction, mining) are always permanently transferred to the Forest Bank, implying that the land will stay forest forever. The landowners can continue to hike, hunt, pick berries and mushrooms and collect firewood as long as it does not hamper forest health and growth and decrease environmental values. The innovative element of the Forest Bank program is that it is voluntary, market-based and accounts for forest owner preferences. It gives owners a way to get cash out of their forest without immediate need to harvest and compromise environmental values also in situations where next harvest incomes would be attained in distant future.

Objectives

Preservation of biodiversity (valuable habitats and species)• Ecologically sound forest management that yields reasonable economic return to landowners

• Prevention of erosion and protection of water quality

• Economic viability of local communities

Data and Facts - Contract

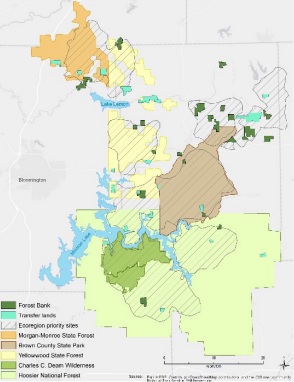

Participation: Indiana Forest Bank has 60 forest owners and covers 3 500 hectares. It operates in two environmentally sensitive locations in southern Indiana, adjacent to several state forests and state parks. Virginia Forest Bank has 2 landowners, covers 9 000 hectares and operates in southwest Virginia, also adjacent to state parks. Both Forest Banks are TNC programs that are managed by its local offices (TNC Indiana, TNC Virginia).

Involved parties:

• Nonindustrial private forest owners (NIPFs), parishes and municipalities (landlords)

• The Nature Conservancy: Forest Bank administrator and operator (tenant)

Management requirements for farmers: Both parties need to accept a forest management plan (stewardship plan). The plan is updated every 10 years; in the absence of owner approval, the previous plan shall remain in effect until a new plan is approved. Forest management operations are carried out by the Forest Bank. FSC certification or other sufficiently demanding green label for forest management is required.

Controls/monitoring: Annual third-party audits (FSC group certification). FSC group certification allows a group of forest owners to join together under a single FSC certificate organized by a group manager. In Indiana and Virginia the group manager is TNC.

Renewal / termination: If contract is fixed-term, renewal is possible every 30 yrs. Termination results in financial penalties (applies to both parties). However, the Forest Bank will always retain land development rights which means that the land will stay forest forever.

Conditions of participation: No minimum or maximum number of participants but operational efficiency (economies of scale) and possibilities for landscape and watershed management increase with the number of participants (“depositors”) and the area enrolled in the Forest Bank.

Links to other contractual relationships: The maximum length of this type of contracts in Indiana and Virginia is 99 yrs (also in Finland, Tenancy Act). Renewal is possible.

Risk/uncertainties of participants: Landowners are able to transfer most of the risks related to forest management and annual payments to the Forest Bank: input and output price risks, risks of natural hazards etc. On the other hand, owners are exposed to default risk as virtually in all forms of deposits. The probability of default depends on e.g. market conditions, legislation, financial solidity of the Forest Bank, terms of deposit withdrawal and length of the contract. The current deposits are guaranteed by The Nature Conservancy. However, there is no guarantee that the Forest Bank can fund early withdrawal requests in short term. This feature is not uncommon in real estate business because real assets are less liquid than for example common stocks and bonds.

Funding/Payments: The scheme is meant to be self-funded in a sense that income (mostly from timber harvests and carbon credits) covers all the operational costs of the Forest Bank as well as annual payments to the landowners. It has also been projected that the timber sold by a Forest Bank could earn a price premium through the use of some kind of green or environmental label. Indiana Forest Bank has been financially supported by the local TNC but the Virginia Forest Bank has reached financial self-sufficiency. An important reason for this is that the latter has sold carbon offsets since 2014; currently carbon payments account 25 percent of its total income. Both Forest Banks have also sold environmentally valuable lands to public (federal and state) entities and through these transactions have received financial income that supports their economic stability.

Problem description

The Forest Bank scheme was developed in the late 1990s by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the largest conservation organization in the United States. The motivation for the novel contract solution was that protection of forests was too slow because acquiring environmentally valuable areas from private landowners required significant amounts of capital that was not usually available for conservation purposes. Working the standard way – preserving nature and protecting biodiversity by buying smaller parcels of land – mostly resulted in fragmented conservation areas that had limited environmental impact; they were not suitable for many imperiled species that required larger natural habitats or for watershed management that required landscape level planning and actions. The acquired lands were often also fairly disconnected from other natural lands. TNC experts recognized that conservation efforts should be redirected to account for limited amount of capital, landscape level requirements, and a new form of integration of economic and ecological objectives that accounts for landowner preferences and viability of local communities. They developed an innovative contract solution, Forest Bank, which i) addresses conservation priorities and local economic needs simultaneously, ii) requires less initial capital because it is based on leases and conservation easements and accounts for landowner preferences, and iii) enables operating at the scale of landscapes and watersheds. The arrangement was named Forest Bank since the underlying idea was that a trustworthy institution holds and manages the tracts of forestland “deposited” by many small holders, then pays these owners a guaranteed rate of return on the appraised value of their timber assets, much as a commercial bank pays interest to people on their savings deposits. The Forest Bank is only available in priority ecological and environmental areas. These are often adjacent to national or state forests and parks, or other existing conservation and recreational areas. An important goal of the Forest Bank program is to establish ecological buffer zones around these areas and ecological corridors between them.

Context features

Landscape and climate: The state of Indiana lies mostly in the temperate zone. It has a humid continental climate with cold winters and hot summers, with only the extreme southern portion of the state lying within the humid subtropical climate, which receives more precipitation than other parts of Indiana. Most forests are located in the southern part of the state. Hardwoods are the dominant species. Most common tree species are maple, yellow poplar, oak, hickory, beech, birch, cherry and ash; conifers are relatively rare. Eighty-three percent of Indiana forestland is privately owned. The state owns 7 percent and the federal government 8 percent. There are four more densely forested areas in Indiana and the local Forest Bank operates in two of them (Brown County Hills and Blue River). The Blue River watershed ranges from the Brown County Hills to the Ohio River, thus the two Forest Bank regions are also environmentally connected. Southwestern Virginia lies in the subtropical zone where summers are hot and winters are moderately warm. The Virginia Forest Bank operates in central Appalachians which area resembles the Brown County Hills and is known for its beautiful landscape, exceptionally high biodiversity, steep hills, and streams and rivers. The location of the Virginia Forest Bank, Clinch River Valley, is home to one of the highest concentrations of rare and endangered species in the United States. Before the establishment of the Forest Bank, TNC ranked the Clinch River Valley watershed first in a scientific evaluation of the biodiversity in all watersheds across the United States.

Farm structure: The Forest Bank is designed for nonindustrial private landowners with a desire to maintain and preserve their forests as forests, on the one hand, and a need for access to its financial value, on the other hand. In Indiana, the average size of forest holding is two hectares and an increasing number of private forest owners are non-residents. Both Forest Banks are committed to use continuous cover forestry (no clear-cuts); they will harvest timber and build roads but in ways that maintain the structure of the forest and its biodiversity. Other main objectives are production of high-quality forests and timber, reintroduction of natural tree species and prevention of invasive species.

Success or Failure?

SUCCESS. Forest Bank has attracted private forest owners and its operations are aimed at

increasing forest biodiversity at landscape level. Although the development has been slow,

he number of forest owners enrolled in the two US Forest Banks has steadily increased since 2002.

Reasons for success :

• Forest Bank offers an innovative, voluntary, market-based and replicable contract solution that combines the protection of biodiversity and ecosystem health with economically compatible forest management on private forestlands.

• The Forest Bank offers a new way to work with landowners that otherwise would not be reached. It is attractive to landowners who value biodiversity and continuous flow of income from an asset (forest) that is generally non-liquid, and who in exchange for these ecological and financial benefits are willing to accept a lower but still reasonable economic return.

• The collection of land is managed by one entity, the Forest Bank, which operates at the scale of landscapes and watersheds and thus can greatly expand biodiversity and other conservation effectiveness.

SWOT analysis

Main Strengths

1. Innovative, voluntary and market driven approach2. Incorporates private landowner preferences related to environment, income and risk

3. Enables landscape level and watershed management

Main Weaknesses

1. Many forest owners are not willing to give up timber and land development rights for 30 years or permanently.2. Requires sufficient land area to achieve operational (economic and environmental) efficiency

3. Attracts only those landowners that are willing to trade (give up) some of their financial return for environmental values and risk aversion

Main Opportunities

1. Can be financially self-sufficient2. May speed and scale up biodiversity and other environmental protection considerably (something that is urgently needed)

3. The arrangement is applicable nationwide in the US and can be tailored to European conditions because many underlying institutions are relatively similar

Main Threats

1. New ideas sometimes collide with habits of thought and the confinements of old laws2. Possible legal and tax complexities

3. Possible difficulties in finding a trustworthy intermediary that holds and manages the tracts of forestland “deposited” by many small holders and is unequivocally committed, and in every way able, to honor the agreements also in the distant future. The concept may not be feasible for smaller organizations

LAND TENURE and VALUE CHAIN and COLLECTIVE

Forest management and/or conservation easement agreement. Green labels and environmental premiums for the harvested timber are used (forest owner – Forest Bank – local sawmills – distributors – stores – consumers and other end-users). Virginia Forest Bank also sells verified forest-carbon credits (forest owner – Forest Bank - firms in the carbon trade system) which can be interpreted as a value chain feature. The contract solution involves several (adjacent) forest owners in the same region.

PUBLIC GOODS

Landscape and scenery

Rural viability and vitality

Biodiversity / (Farmland) biodiversity

Climate regulation-carbon storage

Soil quality (and health) / Soil protection

Resilience to natural hazards

Water quantity (e.g. water retention)

INDIRECT EFFECTS

Improved recreational access and cultural heritage management

LOCATION

Suomi/Finland

Regional, currently applied in two states: southern Indiana (12 counties) and southwest Virginia.

CONTRACT

Contract conclusion:

Written agreement

Payment mechanism:

tradable emission certifications

Start of the program:

2002

End:

still running

Feel free to contact us for any further informations.

CONTACT USLegal notice: The compilation of the information provided in the factsheets has been done to our best knowledge. Neither the authors nor the contact persons of the presented cases may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein.